Blog: Mediterranean research cruise, 2021

NESSC-researcher Addison Rice (Utrecht University) set out on a week-long research cruise in the Mediterranean Sea. Not everything went right…

Day 1 – Boarding the Dallaporto

Day 2 – Deploying a sediment trap

Day 3: 19-07-2021

Reaching the harbour

After deploying the first mooring we sailed south, sticking to the coast where the waves stay small. Even so, the captain steered us into harbour on the third night, deeming the waves too high for the ship to safely navigate. We waited until the next afternoon to continue on, making our way to the southern end of Italy.

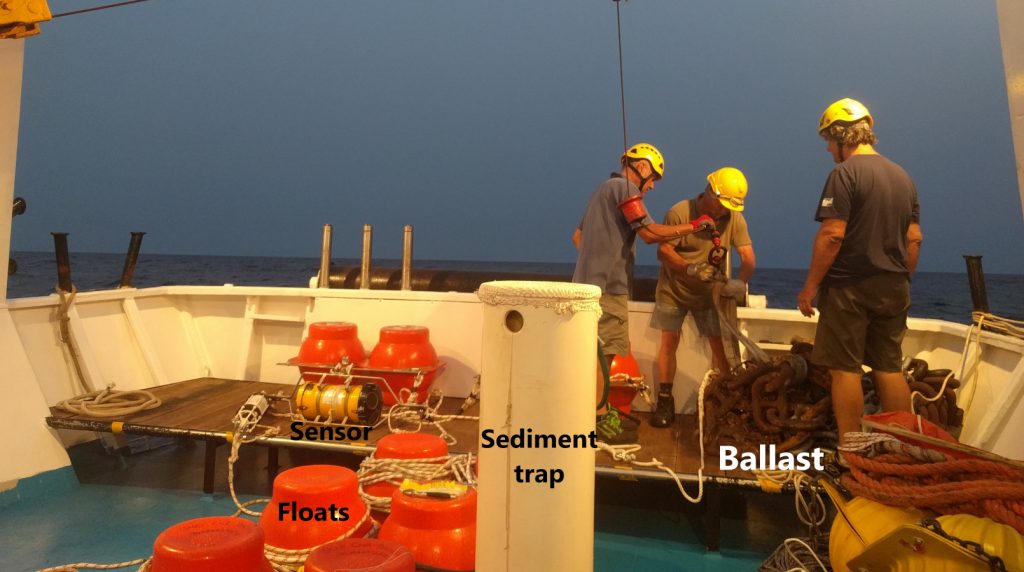

Going toward the open ocean at this point was deemed too risky. Instead of sailing for the MedDust site in the middle of the Mediterranean, we instead went to what was planned to be the third stop of the trip. At this spot off the coast of Catania we deployed a second mooring. This mooring has sensors to determine current direction, temperature, salinity, turbidity, and oxygen content of the water. With these sensors placed at several different water depths, it’s possible to study how the water mixes and moves.

Like last time, the mooring was put together from top to bottom and thrown overboard bit by bit, stretching out far behind us. This mooring was much longer than the first, with over 1500m of cable joining the sensors, floats, and ballast.

MedDust sediment trap

In the end, the weather just wasn’t good enough to safely get to and from the MedDust sediment trap site. This site has hosted a sediment trap mooring since 2013, and is related to a nearby site where sediment traps collected samples from 1991 to 2011. Combined, the old and new sites provide the basis for my research.

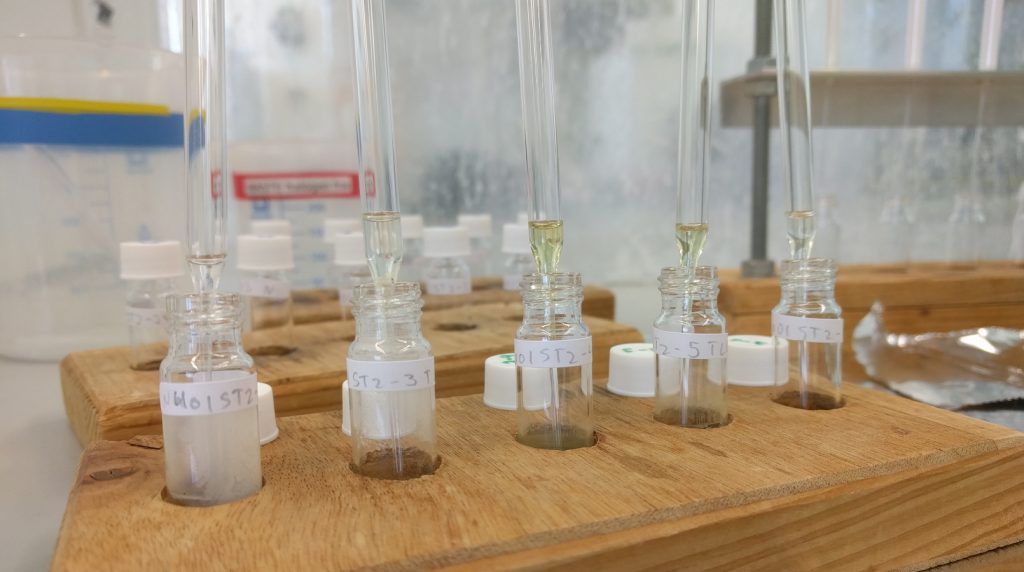

Even though we could not retrieve these samples there’s still plenty for me to work on back in the lab. In fact, most of my days at Utrecht University are spent in the lab. I weigh the samples, measure different chemical components, and put them under the microscope to see what kinds of plankton have fallen into the trap. I’m slowly putting together a picture of how these different components change over time and through water depth.

The winds are strong now, making the waves offshore unsafe for the Dallaporta to navigate. But, we’re planning to return in September, hopefully with better weather. In the meantime, I get a few extra days in the Sicilian sun! All’s well that ends well.

Day 2: 16-07-2021

Deploying a sediment trap

Unlike many oceanographic cruises, our course has mostly kept us close to the coast, giving us amazing views of the Adriatic coast and the chance to spot a few dolphins!

But, the reason we’ve been sticking to the coast is because of high waves further out. The weather pattern over Italy right now is unusual for summer, creating strong winds. Since the Dallaporta is just 36m long, there’s quite a bit of rocking in even small waves.

Fortunately we were able to wait out the wind. The sea became calm in the late evening, allowing us to deploy our first mooring off the coast of Gargano. This mooring, like the one I’m interested in, is a sediment trap. But there’s more to the mooring than the sediment trap itself.

Deployment

At the bottom of the sea there’s the heavy ballast to anchor it in place. In this case, a heavy bundle of old, rusty chains. Above this is an acoustic release, which lets go of the ballast when it receives our signal. That lets us recover the expensive instruments, samples, and data when we’re ready to come back. Then there are floats, made of hollow glass spheres inside of plastic casings. Although these are heavy, the vacuum inside makes them buoyant and they can withstand the immense pressures of the deep sea. Instruments for measuring the temperature, salinity, and turbidity are also along this line, along with the main feature, a sediment trap. More floats above the sediment trap keep everything upright in the water.

In order to get this all into the water and not tangled up on itself, we throw the top floats overboard first, then everything down the line so that it was slowly dragging behind the ship. When we passed the exact location where we wanted to deploy the trap, the ballast is released, splashing into the water. Everything sinks down with it in just the right spot.

Carousel

Of course, I haven’t explained what a sediment trap actually is. As the name suggests, it collects sediments, but how? And why bother?

The trap itself consists of a cone, a programmable motor, and a rotating carousel that turns to change which sample bottle is open. Sediments fall through the cone into the open bottle. Then, at the programmed time, the motor turns the carousel so that the old sample bottle is closed, and a new one is open.

Sample intervals are usually ten or fifteen days. This means that we can compare the data generated from these sediment trap samples with satellite data, including sea surface temperature, surface chlorophyll concentrations, and the timing of Saharan dust storms.

Studies from sediment traps give us an idea of what’s going on through time and through depth in the ocean. Most ways of studying the ocean give us just a snapshot in time, or in the case of satellites, an understanding of the very surface of the ocean.

Although it can be expensive to go to a sediment trap location each year to pick up the old samples and put in fresh bottles, this is one of the best tools to understand the processes that happen through time in the deep ocean.

Day 1: 12-07-2021

Lucky…

I boarded the research vessel Dallaporta today in Ancona, Italy, which will soon be under way to service three moorings in the Mediterranean Sea. For many scientists, myself included, field work and research cruises were postponed in 2020. Still, I consider myself one of the lucky ones. Although I couldn’t get out to sea last year, I’m on a ship now!

One of the moorings we’ll visit this week is the focus of my PhD studies at Utrecht University. It’s a sediment trap in the middle of the Ionian Sea. Really, if you just look at a map of the Mediterranean and point to the spot that looks like it’s in the middle, that’s pretty much it. That’s where we’re headed. This device collects the stuff that’s sinking in the ocean, like the remains of algae and plankton and the wind-blown dust that settles over the ocean.

Along with the captain and crew, two scientists from NIOZ, Wim Boer and Yvo Witte, are here with me to service the MedDust sediment trap. This trap is part of a long-term study at this location since 2013, continuing a record from a nearby location that collected samples from 1991-2011.

…and not so lucky

Sometimes when you’re in the field, things just go wrong. This time it happened before even getting onto the ship.

It’s a standard story: I flew to Bologna, and somehow my bag had made its way to Budapest. With a 30 hour estimate for my bag to get to the Ancona port and the ship leaving in less than 24 hours, there was no way to make it work. I won’t see my suitcase until we’ve reached Sicily, more than a week from now.

In the meantime, I needed something to wear. I spent my morning in town grabbing as many comfortable clothes as I could. Forgive me if I look like a brand ambassador for Champion and H&M.

Will it be smooth sailing from here? By Dutch standards, the weather looks fantastic. But by Italian standards, not so much. Even though it’s summer we’re expecting a little rain, and there might be a thunderstorm tomorrow. We’ll find out soon what luck has in store…