Melting of Greenland ice is at fastest rate in 350 years

Melting at the Greenland ice sheet is at its fastest rate in 350 years, a new Nature-publication finds. Climate researchers reconstructed 350 years of Greenland ice melt, based on melt records from three ice cores drilled in central west Greenland. NESSC-researcher Michiel van den Broeke and postdoctoral researcher Brice Noël, both at the Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research of Utrecht University (IMAU), played an important role in the study by contributing an advanced polar climate model.

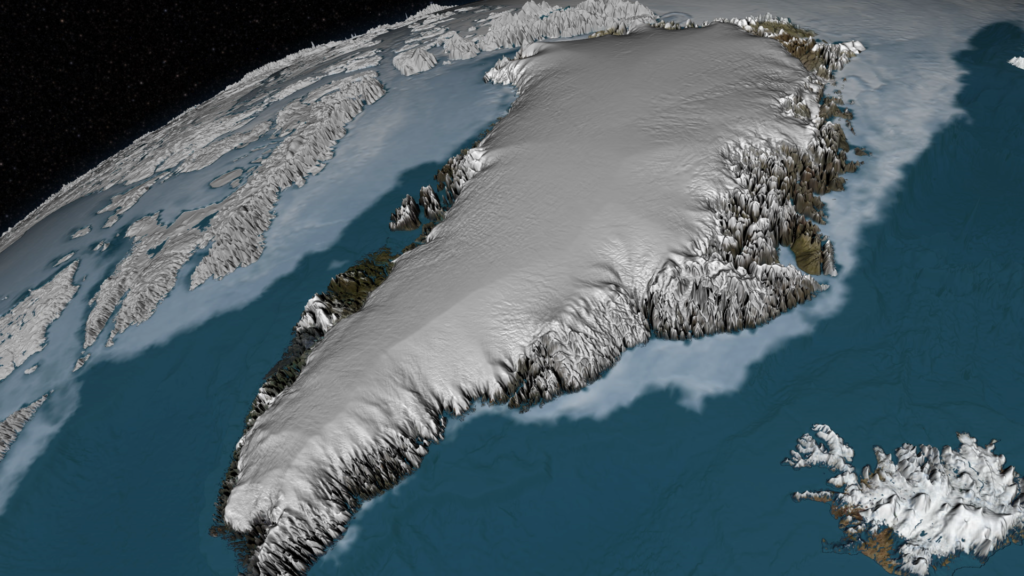

Surface melt on the Greenland ice sheet – the second largest body of land ice on earth – began to increase after the onset of the industrial-era in the mid-1800s and ramped up dramatically during the 20th and 21st centuries. The ice sheet now contributes significantly to global sea level rise. In this study, scientists from the USA and Belgium worked together with Brice Noël and NESSC-researcher Michiel van den Broeke (IMAU, Utrecht University), who contributed an advanced polar climate model that extrapolated the melt from the ice core locations to the entire Greenland ice sheet.

Ice cores

The basic data for this study were derived from three ice cores drilled in the ice of central west Greenland by the research team from the USA. In this part of the ice sheet all surface melt refreezes in the snow, preserving centuries of local melt history. Noël explains: “Every year in summer, the top layer of snow melts and this meltwater percolates downward in the snow, where it refreezes. In the cores, you see this as a layer of ice with a higher density surrounded by snow. The thicker the ice layer, the more melt occurred during that specific year.”

A Greenland melt history from the last 350 years is stored in those ice cores. Noël: “Prior to the satellite era in 1978, estimates of Greenland melt remained highly uncertain. As a result, no conclusions could be drawn for the centuries when modern methods weren’t available yet.” The three ice cores, however, revealed valuable information on the local amount of melt since the 17th century that could be used to estimate surface melting over the whole ice sheet back in time.

Polar climate model

To translate the melt history stored in the three ice cores to the whole of Greenland, an advanced polar climate model proved essential. Noël says: ”Our climate model was used to extrapolate that local melt information from the ice core sites to the full Greenland ice sheet. Because the model reaches a kilometer resolution, we could even determine how small glaciers on the jagged coastline of Greenland have responded.”

Noël: “It turns out that the amount of melt has been increasing since the middle of the 19th century, with a dramatic intensification in the last two decades.” The reason is that Greenland ice sheet melt is highly non-linear; this means that when it gets warmer, it takes an ever-smaller temperature increase to cause the same increase in melt. Noël concludes: “This study proves that warming today means a larger increase in ice melt than it did in the past.”

Article:

Nonlinear rise in Greenland runoff in response to post-industrial Arctic warming

L. D. Trusel, S. B. Das, M. B. Osman, M. J. Evans, B. E. Smith, X. Fettweis, J. R. McConnell, B. P. Y. Noël, M. R. van den Broeke

Nature, 2018